When the Chesley hospital was closed in 1976, the town held a funeral procession led by the mayor, who donned a kilt and piped a lament.

After a few months and significant public outcry, the provincial government reopened the hospital.

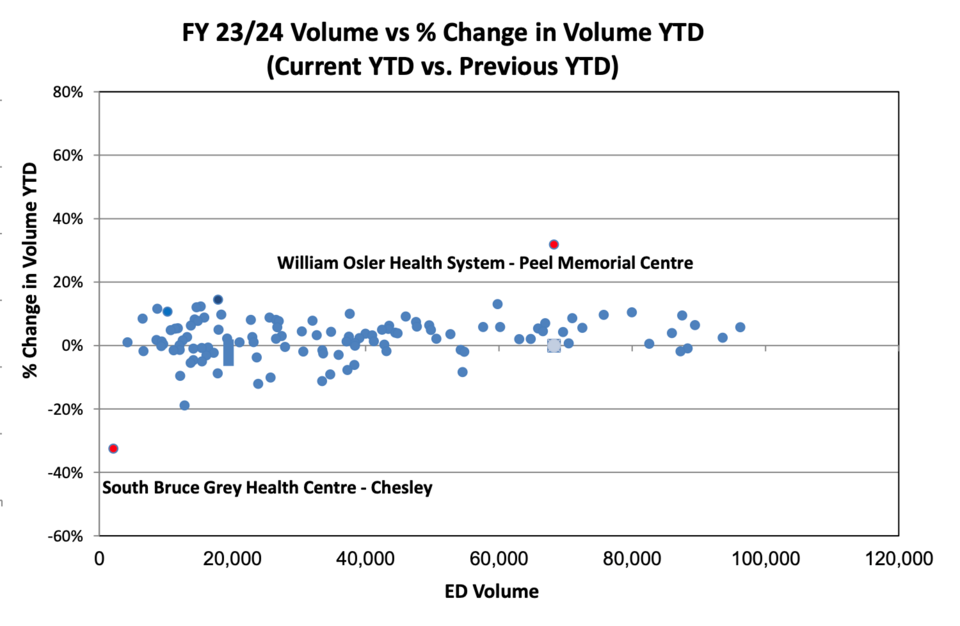

Nearly a half-century later, the hospital is going through tough times again. Its emergency department is operating on reduced hours and is frequently closed on an ad hoc basis. As a result, patient volumes are down — by 33 per cent in December compared to the year prior, according to Ontario Health data obtained by The Trillium.

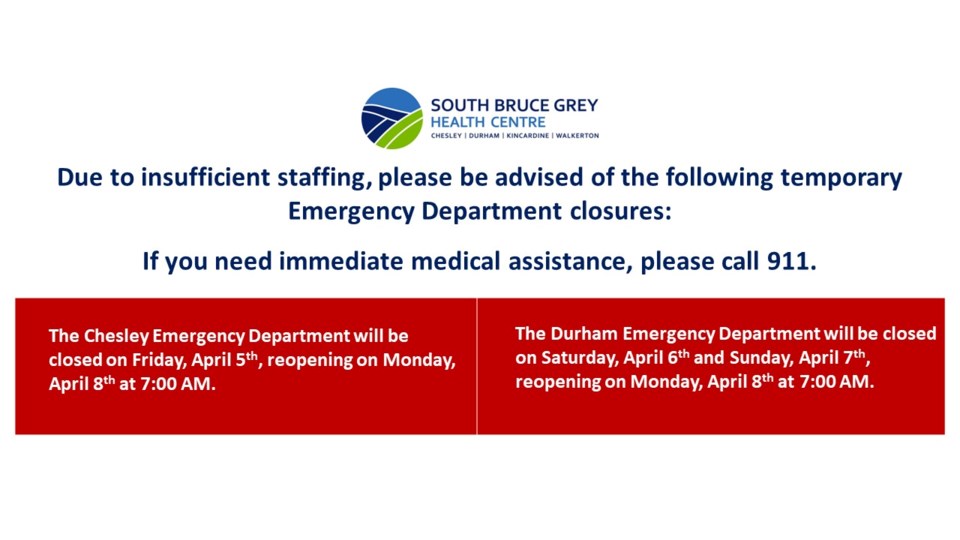

The South Bruce Grey Health Centre (SBGHC) board has counted 429 closures of its four emergency departments over the first 11 months of the last fiscal year — but it's mostly at Chesley, as it includes every day that an emergency department has been closed or operating on reduced hours.

A document obtained by freedom of information request shows that of all of the province's hospitals, Chesley stands apart from the pack in losing emergency department patients.

"Patients, I feel, are going to other hospitals where they know they're consistently open," said South Bruce Grey Health Centre (SBGHC) President and Chief Executive Officer Nancy Shaw in an interview with The Trillium.

Shaw said she doesn't believe people are going without medical care — there are a number of small hospitals with emergency departments in the region. The closest, in Hanover, is a 20-minute drive away and does not close its doors. Another, the one SBGHC oversees in Durham, is also now on reduced hours and experiencing unplanned closures due to staffing shortages.

Shaw said the closures are due to a shortage of registered nursing staff. Overall, SBGHC is short 24 full-time equivalent positions across its four hospital sites, just over a quarter of its budgeted staff, and uses agencies to fill shifts with temp nurses, at a cost of $800,000 in the last fiscal year, according to its board.

That's only possible when temps are available, Shaw said.

The Chesley emergency department remains open during weekday working hours and no decisions have been made about its future, said Shaw.

"Our focus is on providing access to care for all of our communities," she said. "It is important to maintain an access point, just given the geography of the area. So what that looks like in the future — we'll have to work with everyone, all our stakeholders, to vision for the future."

When other hospitals have closed in Ontario — including in Minden last year and in Niagara a decade ago — they have been replaced by urgent care centres that handle less critical patients. That option has not been discussed for Chesley, said Shaw, "but certainly we are looking at options as we move into the future to look at sustainability and access to care."

The future must include an emergency department in Chesley, according to Brenda Scott, co-chair of the Chesley Hospital Community Support group.

She fears the drop in patient volumes, caused by the frequent closures, will ultimately be used to justify the total closure of the emergency department, and Chesley will lose its designation as a hospital.

"This community needs these small rural hospitals — they're not an extraneous part of the health-care delivery system in Ontario, she said. "They perform a very valuable function ... to stabilize patients and prepare them if they need for transport to a larger centre for further treatment. It's not something that we can lose and not miss."

Scott's brother lives in Chesley, about a block-and-a-half from the hospital, and had a massive heart attack at 4 p.m. one day, an hour before the emergency department was set to close at 5 p.m., she said.

"He was sitting in his chair, and he managed to dial 911. The ambulance guys came and immediately took him to the Chesley ER — it was open," said Scott.

He was stabilized and then rushed — by ambulance because a helicopter wasn't available — to Kitchener for surgery and is in recovery today.

"We were told by his physician that he would not have survived the trip to Hanover," she said, referring to the next-closest hospital.

Even in less urgent circumstances, the frequent closures are causing a lot of uncertainty in the community. Often, when people need care, they're not sure if the emergency department is open, and some will call an ambulance they wouldn't otherwise need to ensure they're taken to an open emergency department, Scott said.

A roughly 20-minute drive to the nearest hospital may not be a major problem for people who have cars, but for those who don't drive, including the local Amish community, it is, according to Scott.

Scott blames the root of the problem on factors that aren't unique to the area: the pandemic, combined with provincial wage restraint legislation known as Bill 124 that has since been overturned by the court, led to an exodus of staff, which in turn piled more pressure on those who remained.

"I remember one of the nurses told me she was tired of going home in the evening crying, and she quit her job," said Scott. "And these were health-care professionals who had worked there for years, the pride of our community. They knew everybody, but they just couldn't take it anymore."

According to Shaw, more money wouldn't solve the staffing problem because there are simply no nurses available, but she has hopes that the province's efforts to expand nurse education will eventually increase the pool the hospital can hire from.

That's not to say the hospital isn't under financial pressure: it is.

A director's financial report to the board on Wednesday said SBGHC was running a deficit of $560 million as of the 11th month of the last fiscal year due to incremental wage rates and overtime. This was even after the province reimbursed the hospital for retroactive settlements it had to pay workers when the wage-restraint law was overturned and provided funding for agency staff to fill shifts, which costs more than filled staff positions.

SBGHC doesn't have the full details of its 2024 budget, but hospitals are getting a four-per cent baseline increase overall. The board heard that it will be a "difficult budget" because of the deficit position and that SBGHC's costs are going up by far more than four per cent.

Asked about the financial pressures in an interview the day before the meeting, Shaw said SBGHC is focused on providing high-quality patient care,

"So, if you're a patient in a bed, the impact to you would not be noticeable," she said. "That's our hope."