NEWMARKET - On the same day that Facebook banned six far-reaching, Canadian far-right groups and individuals from its platform, local parents and teachers heard from hate experts that members of such extreme white nationalist organizations had recently targeted Newmarket High School for recruitment purposes.

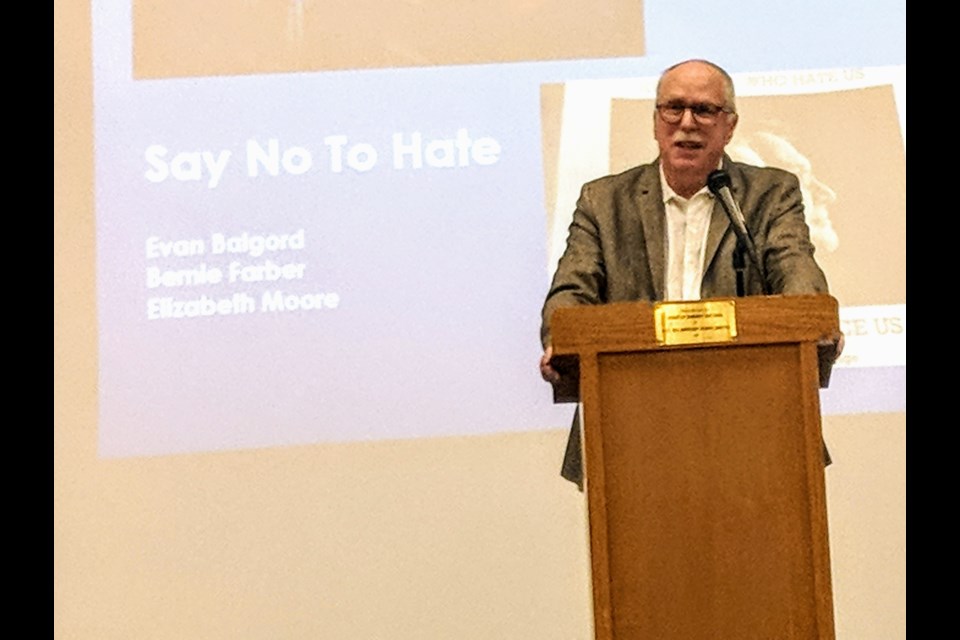

The Say No to Hate seminar organized by the York Region District School Board drew a large crowd of educators, parents and some high school students to the Newmarket High School auditorium on April 8. About 300 people pre-registered for the event.

Moderator Bernie Farber, a longtime human rights and hate crime expert was joined by Elizabeth Moore, a former member of the now-defunct 1990s white supremacist group the Heritage Front, and Canadian Anti-Hate Network executive director Evan Balgord, an investigative journalist and noted researcher on far-right extremism in Canada.

“It’s an important day. Today, Facebook actually decided to act on its promise and bar white nationalist groups and individuals,” Farber said to applause during his opening remarks.

“Tonight, we’re going to talk about hate. We’re clearly living in very complex and difficult times. Even this morning, we were informed that this school was plastered with posters from a white nationalist organization telling people to be aware of the fact that we’re here tonight to talk to you about 'anti-European hatred'. But the sadness is that they came into this school. They’re here, my friends, they’re here.”

Moore, one of the few prominent female spokespersons for the Heritage Front during the height of the neo-Nazi movement in Canada, pulled no punches in sharing her own personal story of radicalization and falling into an all-consuming life of hate that dominated her early high school years into university.

“I was shocked at how far along I was in my radicalization process before I even met (the Heritage Front),” Moore said. “I was a full-blown, raging white supremacist just by reading articles, listening to telephone hotline messages and hanging around with the skinheads at school. That’s it, that’s all it took.”

Her own story is a cautionary tale of warning signs of which parents and educators should be aware. In hindsight, Moore said she displayed all the signs that made her vulnerable to extremist views at about 15 years old. Some of those categories include relational, social identity, personal, and psychological.

“The first one was definitely anger, I was angry all the time,” Moore said. “But of all the teachers I interacted with during my radicalization, only one thought there was a problem and flagged it to my parents, who didn’t understand what to do with that.”

Moore also withdrew socially and drastically changed the way she looked; she cut her hair short and wore all black. She said she was one of the few white students in her Scarborough school and was being bullied because of her fair skin. Her sense that life was unfair began to overtake her thoughts.

Moore confided her feelings to a friend, who handed her a flyer of a group he was involved with, the Heritage Front, which professed to have a mandate to protect the rights of “Euro-Canadians”.

“I just ate it up,” she said. “I started calling their hotline, read issues of their magazine, and it kind of snowballed from there.”

A key warning sign for parents and educators to be on the lookout for is racist content. Moore said she wrote a poem in high school about the colour white, and spliced in tidbits about white supremacy throughout it. No one thought that was a problem, she added.

Today, most extremist recruitment happens online — on social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, 4chan and 8chan, private chat rooms, and even subtle messages through online video games. Recruiters attempt to lure supporters with mild content, sometimes witty, before sharing more obvious ideas about white nationalism.

“It’s still the same message, still the same hate and it still leads to the same place,” Moore said. “Once you start laughing, as I did, at real-life instances of harassment and assault, you kind of lose your empathy.”

The difference between the radicalization of the 1990s and today, Moore said, is how fast someone can go from zero to hate in the digital age.

“Education is absolutely key, in the classroom and at seminars such as this one,” Moore said. “Teach critical thinking skills to your kids, show them how to cross-reference facts. Address broader social concerns. Put empathy and compassion at the centre of teaching practices.”

Moore said that, for her, hatred was intoxicating and made her feel untouchable.

“It comes out in what you choose to eat for breakfast and what you watch on TV,” she said. “I avoided kosher food and wouldn’t watch TV shows with a person of colour or a Jewish person as the main character.”

Hatred is not benign, racist extremism is not benign and anyone, regardless of how well educated and equipped they are otherwise, can be vulnerable to some sort of extremist ideology in the wrong set of circumstances, Moore said.

“I can’t end on an optimistic note. Not today, not after Christchurch, not right now. An optimistic note lets white people, myself especially, off the hook far too easily,” she said.

“But what scares me even more is the legitimacy that some of today’s politicians, media, and other people in power are giving to hate groups. They are normalizing hatred and it’s creeping into our mainstream and it horrifies me. More people are embracing racist extremism as never before.”

In a similar vein, Canadian Anti-Hate Network executive director Evan Balgord, said a goal of the new alt-right, neo-Nazi movement is to push their ideas into mainstream discourse. In Canada, there are two different far-right extremist movements, one is the anti-Muslim movement, which includes neo-Nazi groups, and a separate alt-right neo-Nazi movement, which has recently shown up in local high schools here and in Toronto.

“It is deadly. They believe that they’re fighting a culture war, and their goal is not to take immediate power, their goal is to move what ideas are acceptable to be discussed in mainstream society,” Balgord said.

“Should that happen, what does that mean for Canada? They (white nationalist hate groups) were encouraging their supporters to join the Conservative Party of Canada, to vote for and support Doug Ford, and Maxime Bernier. For example, they love that Doug Ford never disavowed Faith Goldy completely when he associated with her. They loved it when Bernier would tweet negative things about multiculturism.”

While the alt-right primarily targets women, Jews and Muslims, they have also been known to direct their hate toward the LGBTQ2 community and people of colour, Balgord said.

They are mostly white males, aged 16 to 30, primarily located in Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia, and they number in the high hundreds to low thousands online.

“One of the key differences today is that these kids are far more upwardly mobile than skinheads, who wore their ideology, such as with tattoos and swastikas,” he said. “Today, they don’t. They may have fascist-looking haircuts, but they don’t have any kind of identifying features anymore.”

And, according to Statistics Canada, the group committing the most hate crime is children under 18, Balgord added.

While there are exceptions, those at risk of radicalization are generally white, young men who may feel they don’t have a chance with women, oppose ‘political correctness’, engage in hateful or racist speech to trigger a reaction, and experience social isolation outside their online communities, Balgord noted.

“When somebody talks about white nationalism, the end of that ideology is mass murder,” Balgord said. “White nationalism calls for a white Canada or white America, and that would require mass deportation or mass murder.”

Balgord offers these tips to help prevent young people from being radicalized:

- Teach critical media/digital literacy skills

- Humanize their targets

- Teach values early and often, solidarity with other people, respect for diversity, human rights, and learning to live together

- Counter narratives with facts

What can you do if your child is involved with a far-right hate group?

- If they are participating, they are already hurting people

- White nationalism calls for mass violence

- Anticipate challenges, they may come with “facts” and rhetorical arguments

- Contact experts in the subject matter, such as antihate.ca, and deradicalization experts such as Life after Hate

- Limit hate propaganda at its source